Bacteriophages, often referred to as phages, are viruses which infect and kill bacteria. Unlike other viruses such as COVID-19, phages do not infect or damage human cells, enabling us to utilise them in therapeutics to treat bacterial infections.

Phages are becoming increasingly important in medical sciences, with the hope that these viruses could be utilised to eliminate bacterial infections, particularly those which are resistant to antibiotics.

What are phages?

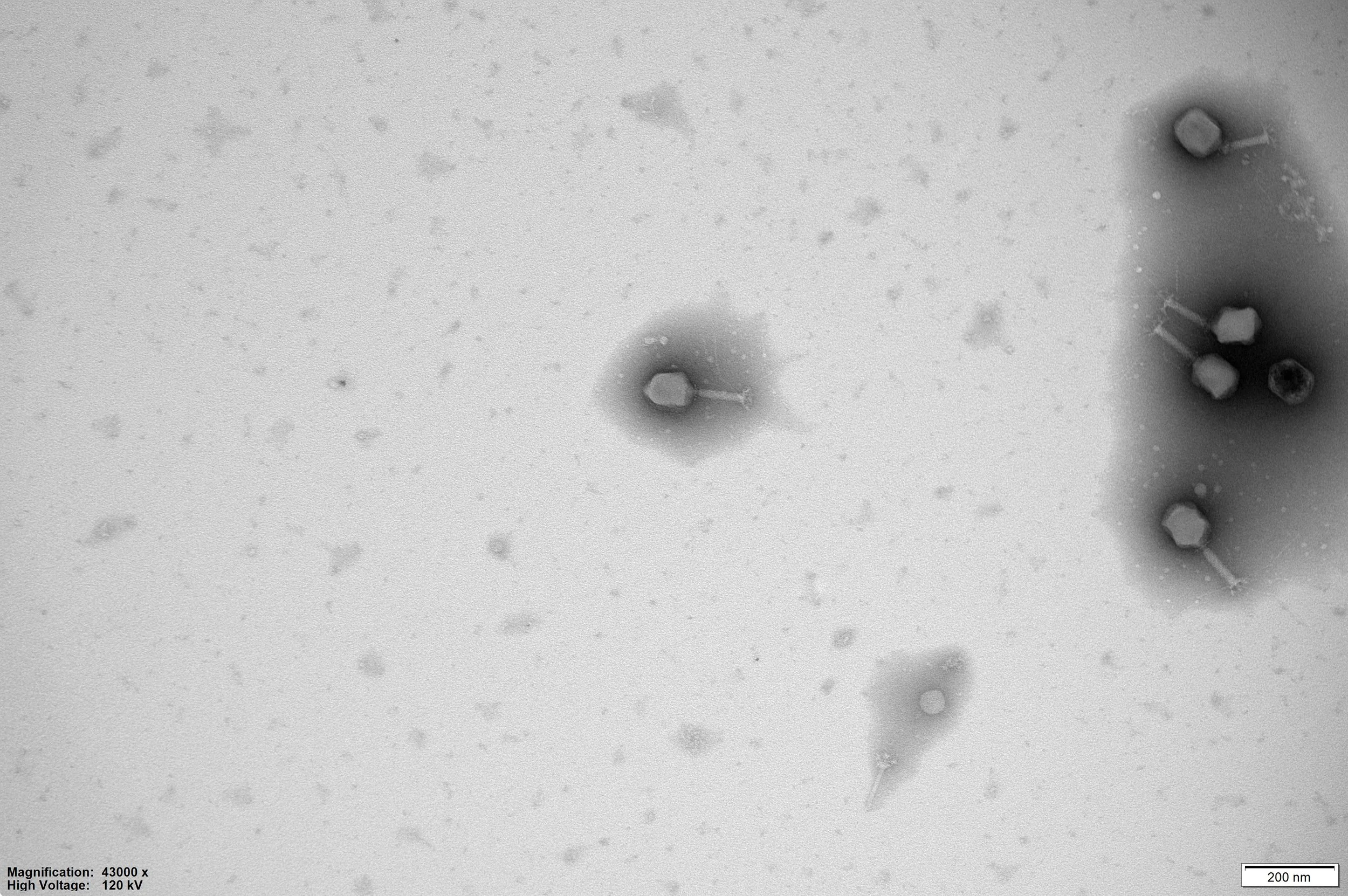

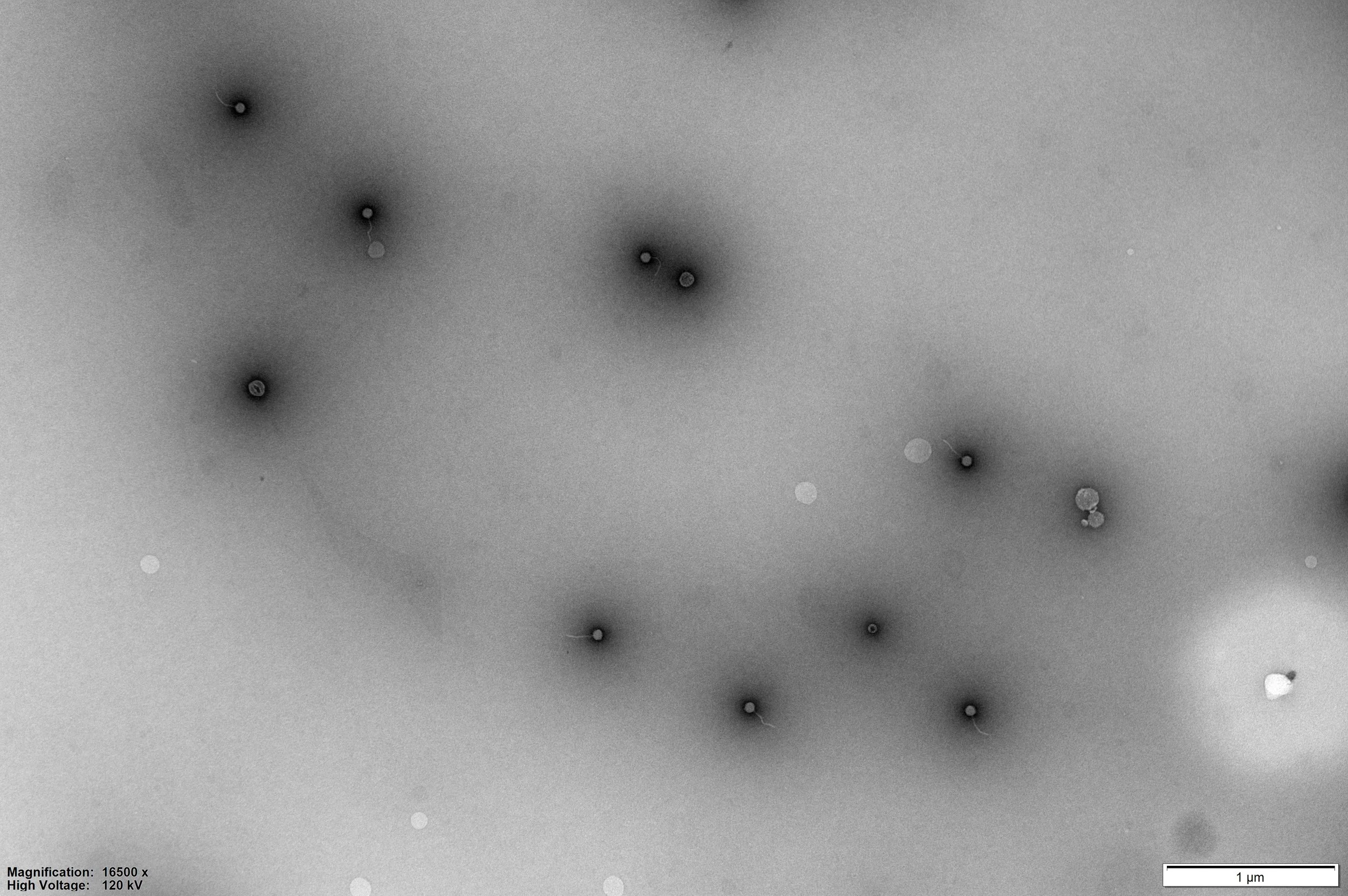

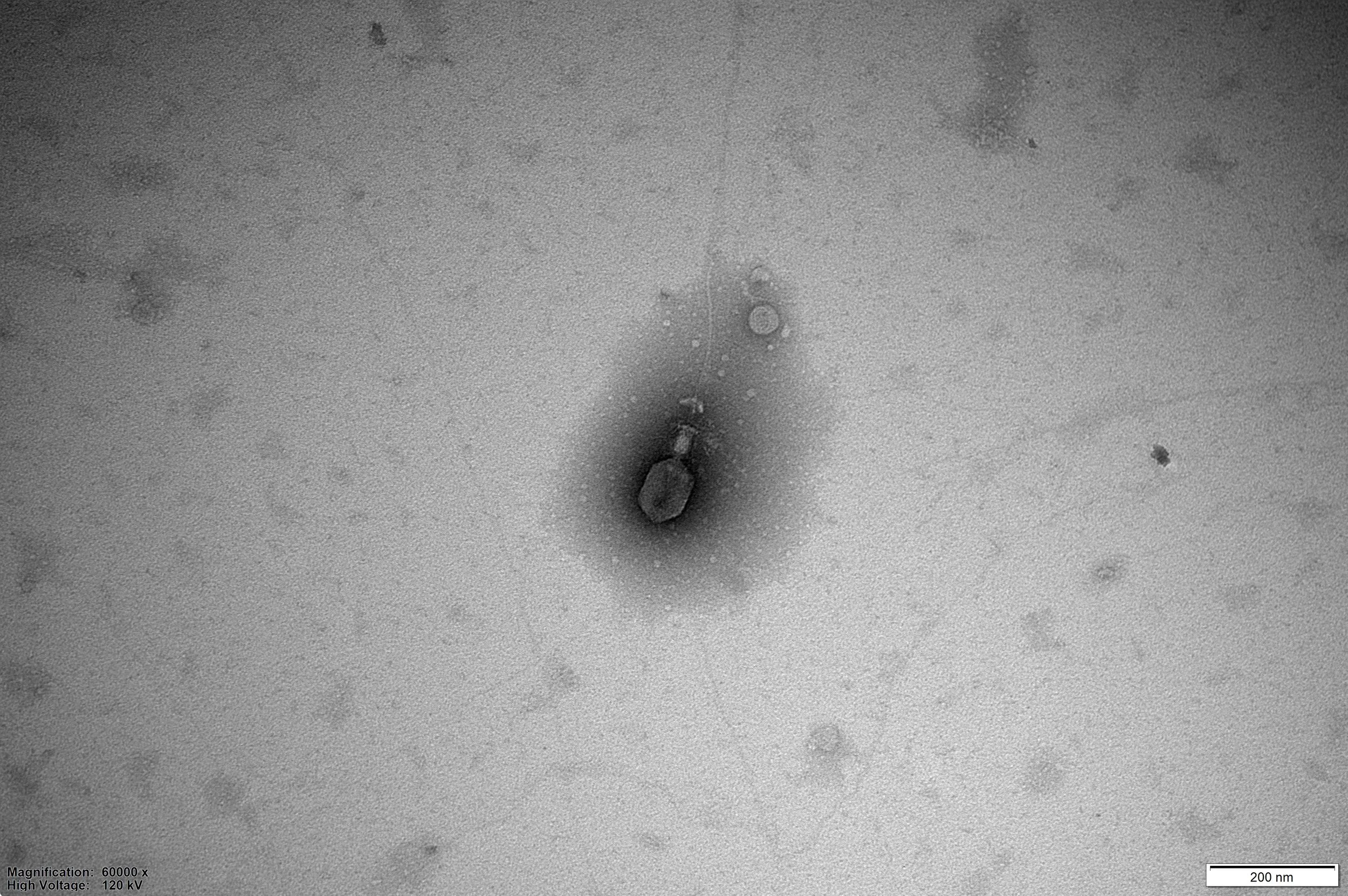

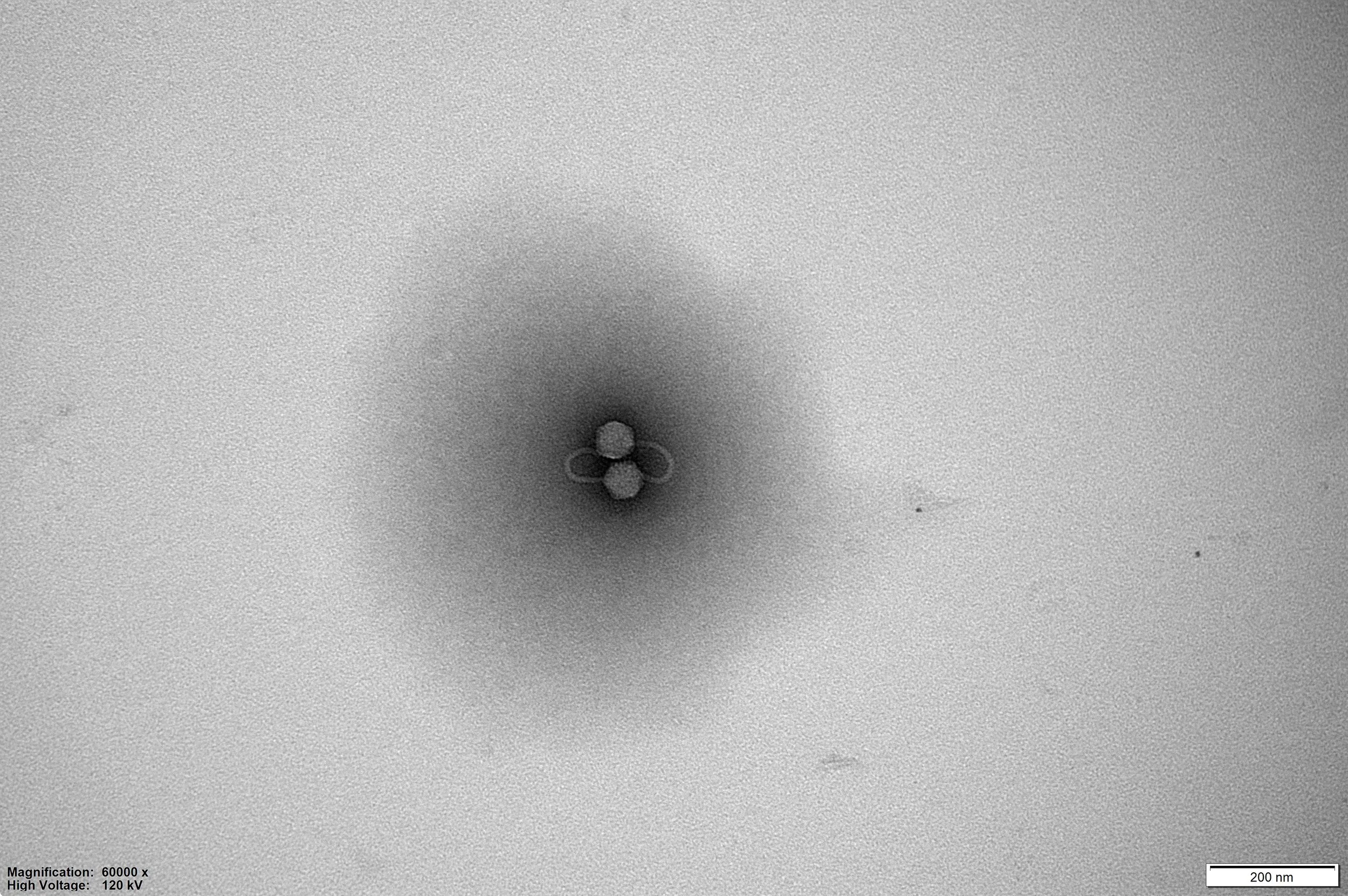

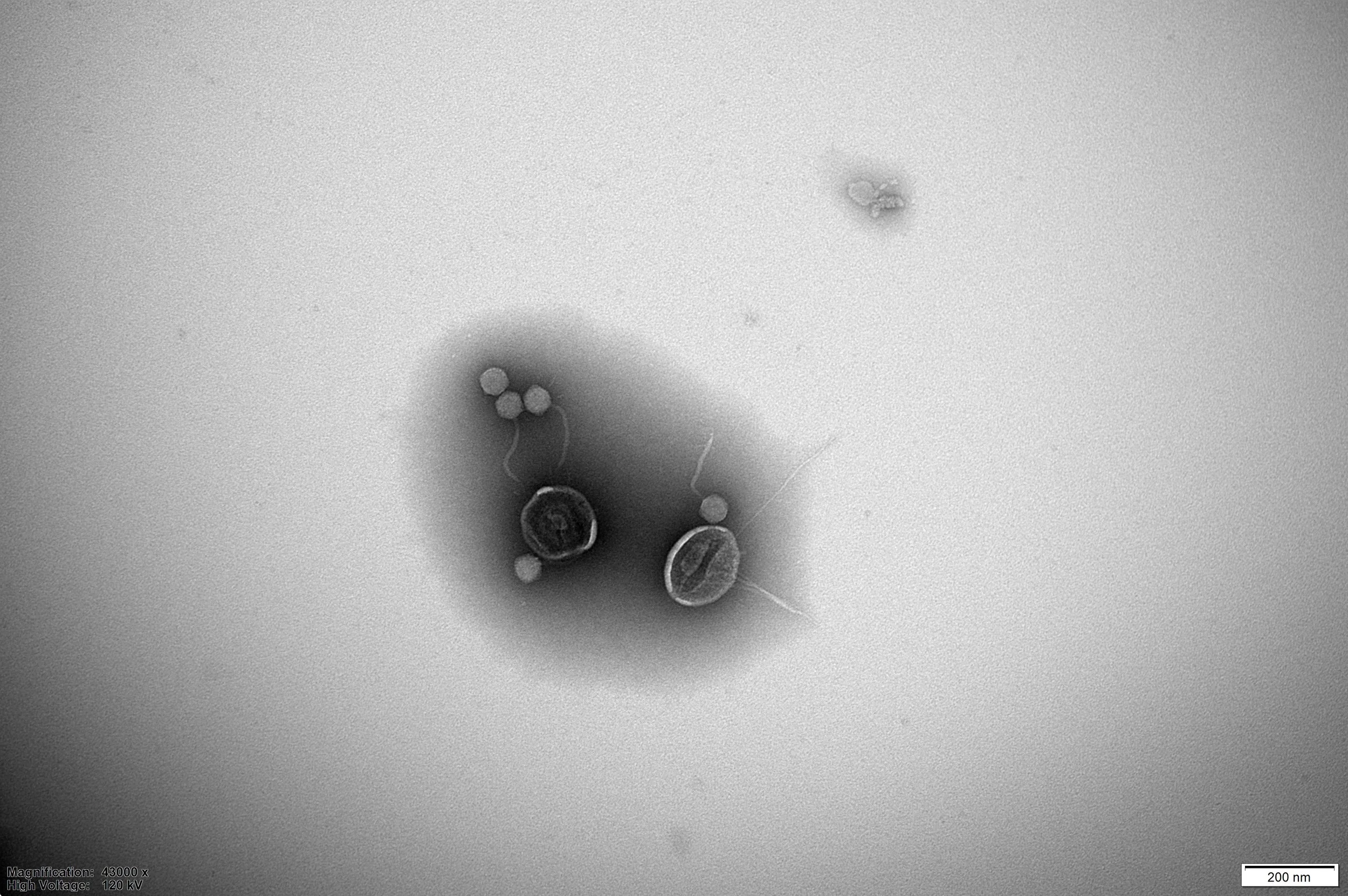

Check out some phages isolated by PhD student Daniela Rothschild Rodriguez as part of KlebPhaCol collection below.

Where can we find phages?

Phages are the most abundant biological entity found on Earth, estimated to outnumber bacteria 10 to 1(1). They can be found in any environment where bacteria reside, such as the world’s oceans, soils and lakes.

These tiny entities also naturally exist in our bodies. Phages have been detected in the human gut, lungs and skin, playing an important role in controlling bacterial populations throughout the human body.

What do phages look like?

Caudoviricetes is the class of phage that are typically isolated in the highest abundance(2). Within this class there are various phage morphologies that we can observe including myophage, siphophage and podophage.

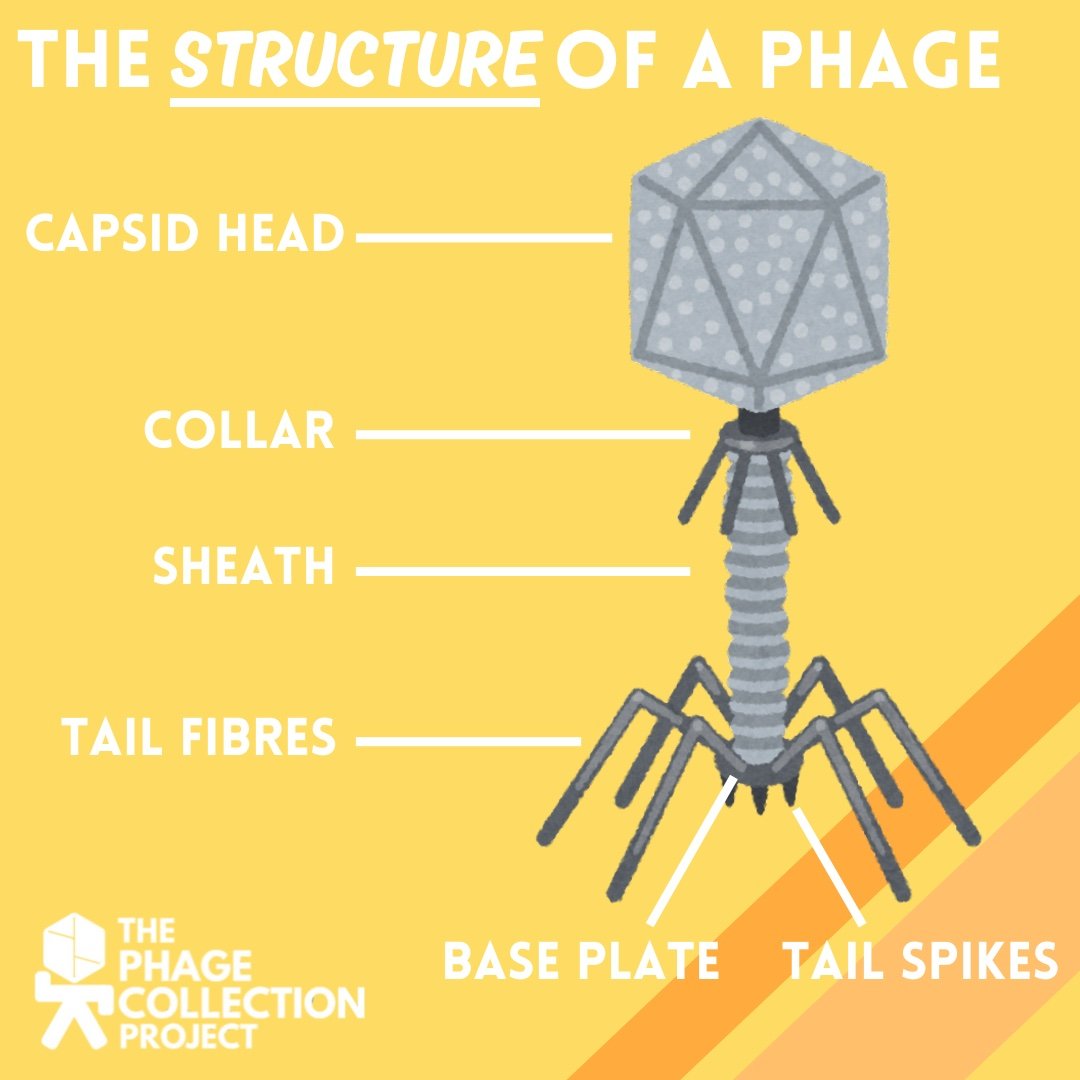

Each of these phages share structural components essential for their survival and replication:

Capsid: Contains and protects the phage’s genetic material.

Collar: Connects the capsid and sheath together and controls the release of the phage’s genome from the capsid upon injection.

Tail fibres: Interact with the bacterial cell membrane to determine if it is a suitable host for the phage.

Base plate: Meets the bacteria’s cell membrane and enables the phage to inject its genetic material into the host cell.

Tail spikes: Recognise and bind to receptors on the bacteria’s cell membrane.

Phages are extremely small. To view them we use a transmission electron microscope.

When were phages discovered?

Whilst not described, the action of phages is first thought to have been observed in 1895 by bacteriologist Ernst Hankin, when analysing the waters of the Ganges and Jamuna rivers(3). Two decades later, phages were described independently, in 1915 by William Twort and then in 1917 by Felix d’Herelle(4). They have been applied therapeutically for over a century, first utilised by d’Herelle in 1919 to treat patients suffering from dysentery(5).

In 1928, when antibiotics like penicillin were discovered, phage therapy received less attention in the Western world, however in Eastern Europe they continued to investigate these viruses. Due to the global health crisis posed by antimicrobial resistance (AMR), interest in phage therapy is returning.

How do phages infect and kill bacteria?

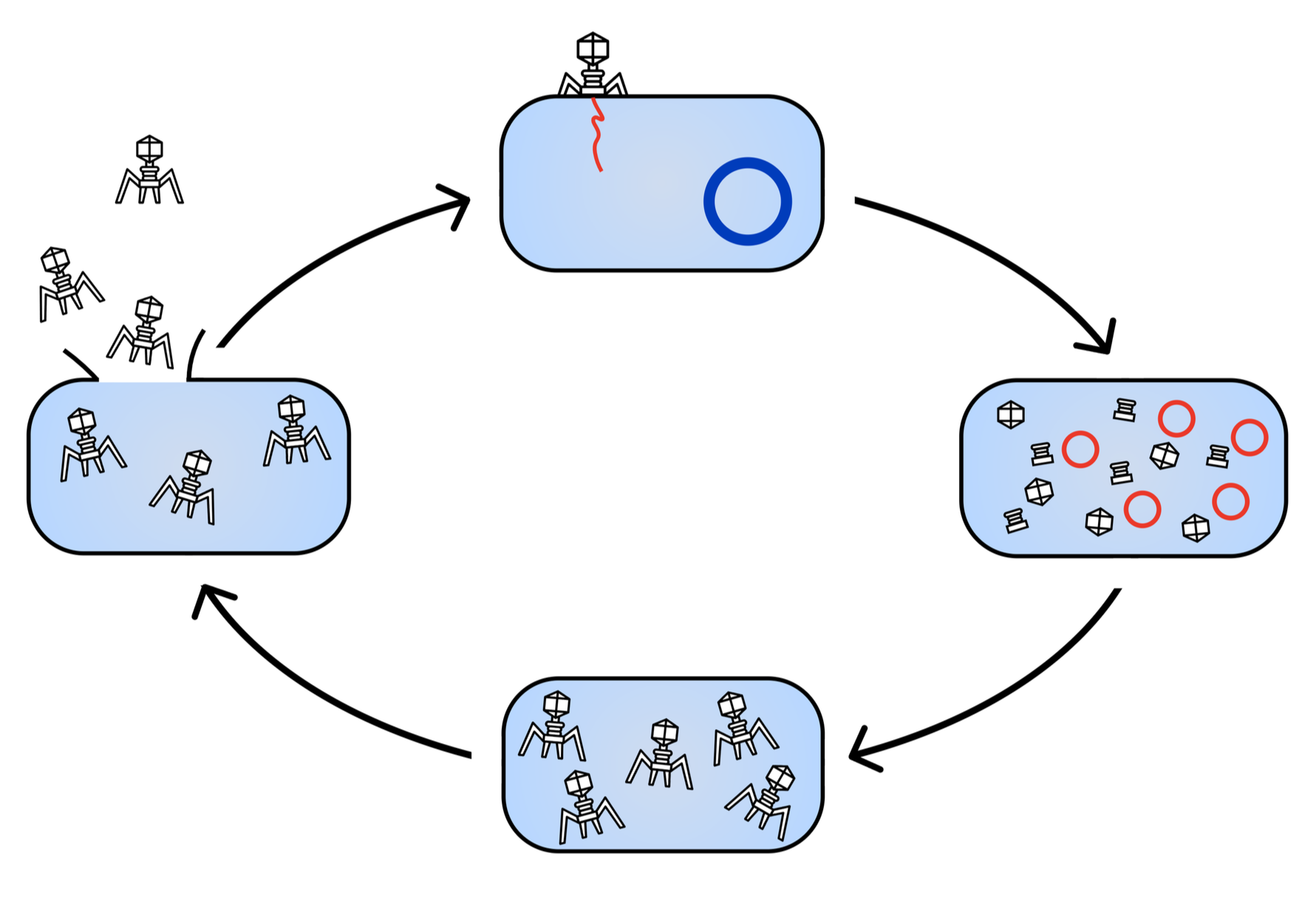

Phages infect and kill bacteria through a process known as the lytic lifecycle.

A phage encounters, recognises and binds to a bacterial cell using its tail fibres, which recognise receptors on the surface of the bacterium.

Once bound securely, the phage injects its genetic material into the bacterium.

The phage hijacks and takes control of the cell, replicating and manufacturing each of its structural components within the bacterium.

Once all the structural components are created, they assemble to form a fully functional phage.

The phages produce molecules known as enzymes which degrade the bacterial cell wall and membrane, causing the bacteria to die and releasing the phages into the surrounding environment.

References

(1) Bergh, O. Børsheim, KY. Bratbak, G. Heldal, M. Nature 1989. High abundance of viruses found in aquatic environments.

(2) Garin-Fernandez, A. Pereira-Flores, E. Glöckner, FO. Wichels, A. Marine Genomics 2018. The North Sea goes viral: Occurrence and distribution of North Sea bacteriophages.

(3) Kochhar, R. Notes and Records 2020. The virus in the rivers: histories and antibiotic afterlives of the bacteriophage at the sangam in Allahabad.

(4) Clokie, MRJ. Millard, AD. Letarov, AV. Heaphy, S. Bacteriophage 2011. Phages in nature.

(5) Strathdee, SA. Hatfull, GF. Mutalik, VK. Schooley, RT. Cell 2023. Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions.